See the Pictures of Lake Baikal

at the End of this Page

at the End of this Page

The Ice-Skating Babushka Of Baikal

When this 76-year-old Russian pensioner needs to herd her cows,

she skates across the frozen waters of Lake Baikal to find them.

When this 76-year-old Russian pensioner needs to herd her cows,

she skates across the frozen waters of Lake Baikal to find them.

Hermit Surviving in Russian Wilderness

for 70 years.

for 70 years.

Soon after this film aired, Agafia found a helper who has now been living with her for more than a year. Georgy Danilov, 53, is from Orenburg.

It was Agafia’s spiritual father who found and blessed her helper. Georgy has been doing the toughest chores for almost two years: he chops firewood, brings water from the river, and digs the vegetable garden. Agafia doesn’t always see eye to eye with Georgy.

She views him as a novice and demands his full obedience and submission, which doesn’t always sit well with Georgy. Despite their differences, they try to find common ground.

Apart from the main helper, volunteers and students from various Russian cities also come to Agafia’s hut to help her out. In the mid-17th century, the leader of Russia’s Orthodox Church, Patriarch Nikon, introduced radical reforms in Russia.

Many couldn’t accept the changes and became known as “Old Believers”. To avoid religious persecution first from the Orthodox Church and then from the Soviets, families fled to some of the most remote corners of the world. In 1978, one such family was discovered by a group of geologists in the remote Russian Republic of Khakassia, Siberia.

The Lykovs looked as if they belonged to a previous century: they dressed in homespun clothes and used primitive instruments in their everyday life. They were completely self-sufficient and still highly religious. Today, Agafia, 70, is the last surviving member of this family. When RT Doc filmmakers met her, she was in desperate need of a helper. They encourage her to write a letter to Old Believers everywhere in an attempt to find one.

This letter, written in Old Slavonic language, is available on our site. The film crew also interviews Erofey Sedov, a former drilling geologist. He was one of those who discovered the Lykovs and told the world about them. He got to know them well and is now ready to share information that will make us see the familiar story of this family of hermits in a different light.

It was Agafia’s spiritual father who found and blessed her helper. Georgy has been doing the toughest chores for almost two years: he chops firewood, brings water from the river, and digs the vegetable garden. Agafia doesn’t always see eye to eye with Georgy.

She views him as a novice and demands his full obedience and submission, which doesn’t always sit well with Georgy. Despite their differences, they try to find common ground.

Apart from the main helper, volunteers and students from various Russian cities also come to Agafia’s hut to help her out. In the mid-17th century, the leader of Russia’s Orthodox Church, Patriarch Nikon, introduced radical reforms in Russia.

Many couldn’t accept the changes and became known as “Old Believers”. To avoid religious persecution first from the Orthodox Church and then from the Soviets, families fled to some of the most remote corners of the world. In 1978, one such family was discovered by a group of geologists in the remote Russian Republic of Khakassia, Siberia.

The Lykovs looked as if they belonged to a previous century: they dressed in homespun clothes and used primitive instruments in their everyday life. They were completely self-sufficient and still highly religious. Today, Agafia, 70, is the last surviving member of this family. When RT Doc filmmakers met her, she was in desperate need of a helper. They encourage her to write a letter to Old Believers everywhere in an attempt to find one.

This letter, written in Old Slavonic language, is available on our site. The film crew also interviews Erofey Sedov, a former drilling geologist. He was one of those who discovered the Lykovs and told the world about them. He got to know them well and is now ready to share information that will make us see the familiar story of this family of hermits in a different light.

Surviving in the Siberian Wilderness

for 70 Years (Full Length)

In 1936, a family of Russian Old Believers journeyed deep into Siberia's vast taiga to escape

persecution and protect their way of life.

The Lykovs eventually settled in the Sayan Mountains, 160 miles from any other sign of civilization.

In 1944, Agafia Lykov was born into this wilderness.

Today, she is the last surviving Lykov, remaining steadfast in her seclusion.

In this episode of Far Out, the VICE crew travels to Agafia to learn about her taiga lifestyle and the

encroaching influence of the outside world.

for 70 Years (Full Length)

In 1936, a family of Russian Old Believers journeyed deep into Siberia's vast taiga to escape

persecution and protect their way of life.

The Lykovs eventually settled in the Sayan Mountains, 160 miles from any other sign of civilization.

In 1944, Agafia Lykov was born into this wilderness.

Today, she is the last surviving Lykov, remaining steadfast in her seclusion.

In this episode of Far Out, the VICE crew travels to Agafia to learn about her taiga lifestyle and the

encroaching influence of the outside world.

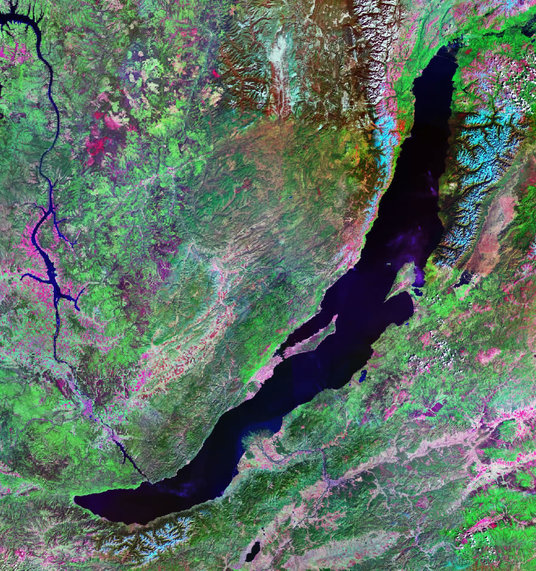

LAKE BAIKAL

A Spot of Silence

There are silent places on Earth, where words are weakened. Words lose their meanings or take on different ones – especially when we try to narrate these places. The wanderer is always alone here,

as he cannot escape this bell formed by the interaction of the self and the place. He stays together both within himself and with the scene.

Baikal is this kind of place, with pine-trees standing bolt-upright and in places birches on the steep hillside, peaks behind us, and the endless water surface ahead. Lake Baikal is a fresh-water sea surrounded by peaks, a legend, at once a pure song of praise and obscene skit, miraculous and banal, crystalline and obscured, gigantic, unapproachable and unprotected, vulnerable,

like the soul of Russia.

If someone wanted to, they could go on and on about all the things they have found out about Lake Baikal. For instance, Valentin Rasputin. ‘I’m still fighting with Baikal, and I can feel my deafness and dumbness – so that I’m unable to put down the things I can see.

Man doesn’t have enough organs to take in the meaning of a miracle like this.’ No one in this earthly life can take in Baikal, and you certainly cannot narrate it. What’s left for us is that we – and maybe the camera – know about it.

László M. Lengyel / Hungary

A Spot of Silence

There are silent places on Earth, where words are weakened. Words lose their meanings or take on different ones – especially when we try to narrate these places. The wanderer is always alone here,

as he cannot escape this bell formed by the interaction of the self and the place. He stays together both within himself and with the scene.

Baikal is this kind of place, with pine-trees standing bolt-upright and in places birches on the steep hillside, peaks behind us, and the endless water surface ahead. Lake Baikal is a fresh-water sea surrounded by peaks, a legend, at once a pure song of praise and obscene skit, miraculous and banal, crystalline and obscured, gigantic, unapproachable and unprotected, vulnerable,

like the soul of Russia.

If someone wanted to, they could go on and on about all the things they have found out about Lake Baikal. For instance, Valentin Rasputin. ‘I’m still fighting with Baikal, and I can feel my deafness and dumbness – so that I’m unable to put down the things I can see.

Man doesn’t have enough organs to take in the meaning of a miracle like this.’ No one in this earthly life can take in Baikal, and you certainly cannot narrate it. What’s left for us is that we – and maybe the camera – know about it.

László M. Lengyel / Hungary