🌸

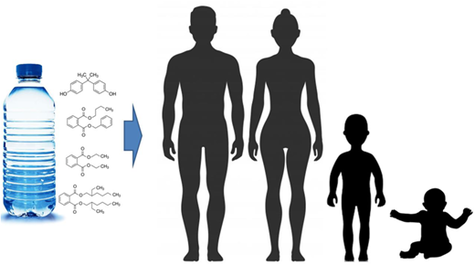

Bisphenol A - BPA

🌸

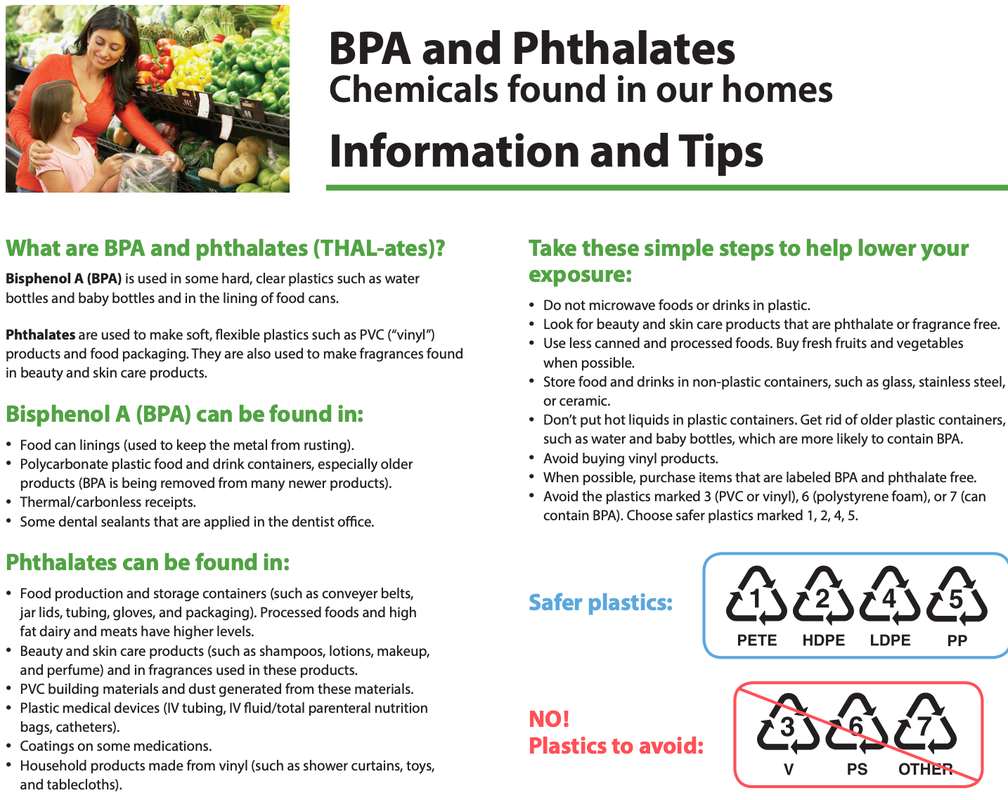

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a chemical produced in large quantities

for use primarily in the production of polycarbonate plastics.

It is found in various products including shatterproof windows, eyewear, water bottles,

and epoxy resins that coat some metal food cans, bottle tops, and water supply pipes.

🌸

Bisphenol A - BPA

🌸

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a chemical produced in large quantities

for use primarily in the production of polycarbonate plastics.

It is found in various products including shatterproof windows, eyewear, water bottles,

and epoxy resins that coat some metal food cans, bottle tops, and water supply pipes.

🌸

🌸

Bisphenols and Phthalates

are

EVERYWHERE

🌸

Bisphenols and Phthalates

are

EVERYWHERE

🌸

🌸

Nanoplastics

🌸

Nanoplastics

🌸

🌸

Average bottle of water

contains

240,000 pieces of cancer-causing nanoplastics ...

100 times more than previously thought.

🌸

contains

240,000 pieces of cancer-causing nanoplastics ...

100 times more than previously thought.

🌸

The world shifted to bottled water due to claims tap water is contaminated

By COLIN FERNANDEZ ENVIRONMENT EDITOR and STACY LIBERATORE FOR DAILYMAIL.COM

Bottles of plastic water contain hundreds of thousands of toxic microscopic plastic particles, new research has found.

The findings are likely to shock anyone who has swapped from tap to bottled water, believing it was better for their health.

Drinking water from a bottle could mean you are contaminating your body with tiny bits of plastic, which scientists fear can accumulate in your vital organs with unknown health implications.

Nanoplastics have already been linked to cancer, fertility problems and birth defects.

Scientists using the most advanced laser scanning techniques found an average of 240,000 plastic particles in a one-liter bottle of water, compared to 5.5 per one liter of tap water.

Drinking water from a bottle could mean you are contaminating your body with tiny bits of plastic, which scientists fear can accumulate in your vital organs with unknown implications for health.

Scientists using the most advanced laser scanning techniques found an average of 240,000 plastic particles in a one-liter bottle of water, compared to 5.5 per one-liter of tap water.

University of Columbia researchers tested three popular brands of bottled water sold in the United States – and, using lasers, analyzed the plastic particles they contained down to just 100 nanometers in size.

The particles – nanoplastics - are much smaller than the microplastics previously detected in bottled water.

However, the particles are considered potentially toxic because they are so small that they can enter directly into blood cells and the brain.

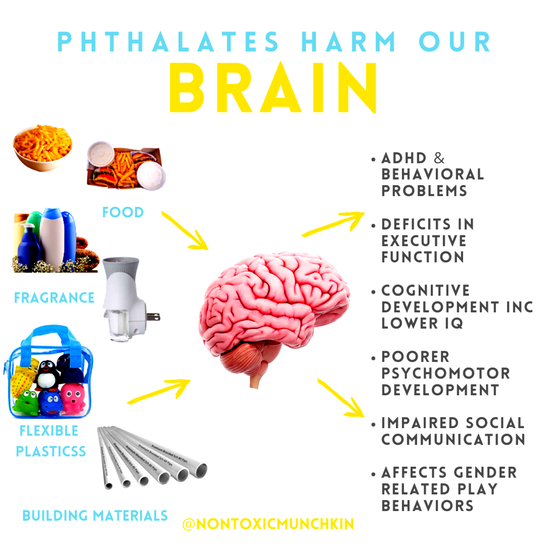

These microscopic particles carry phthalates — chemicals that make plastics more durable, flexible, and lasting longer.

Phthalate exposure is attributed to 100,000 premature deaths in the US each year. The chemicals are known to interfere with hormone production in the body.

They are 'linked with developmental, reproductive, brain, immune, and other problems', according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

The highest estimates found 370,000 particles.

Nanoplastics had been too difficult to detect using conventional techniques, which could only find microplastics ranging from 5mm down to 1 micrometer – a millionth of a meter, or 1/25,000th of an inch. Nanoplastic particles are less than 1 micrometer across.

Groundbreaking research in 2018 found around 300 microplastic particles in a liter of bottled water – but researchers were limited by their measurement techniques at the time.

Research is now underway across the world to assess the potentially harmful effects.

The team used a new technique called Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) microscopy, which was recently invented by one of the paper's co-authors.

The method probes bottles with two lasers tuned to make specific molecules resonate, and a computer algorithm determines their origin.

The results showed that nanoparticles made up 90 percent of these molecules, and 10 percent were microplastics.

One common type found of nanoparticle was polyethylene terephthalate or PET.

Scientists using the most advanced laser scanning techniques found an average of 240,000 particles of plastic in a one-liter plastic bottle of water – thousands of times more particles than had been previously found.

Study co-author Professor Beizhan Yan, an environmental chemist at Columbia, said: ‘This was not surprising, since that is what many water bottles are made of,’ said.

He continued: ‘PET is also used for bottled sodas, sports drinks, and products such as ketchup and mayonnaise.

‘It probably gets into the water as bits slough off when the bottle is squeezed or gets exposed to heat.’

Another plastic particle found in bottles of water, and one which outnumbered PET, was polyamide – a type of nylon.

‘Ironically,’ said Professor Yan, ‘this probably comes from plastic filters used to supposedly purify the water before it is bottled.’

The other common plastics found included polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polymethyl methacrylate, all of which are used in various industrial processes.

The tiny particles made up 90 percent of these particles, and 10 percent were microplastics. One common type found was polyethylene terephthalate or PET.

However, the researchers found ‘disturbing’ that these named plastics only accounted for around 10 percent of all the nanoparticles found in the samples. They have no idea what the rest are.

Biophysicist and study co-author Wei Min said the research opens up a new area in science, adding, ‘Previously this was just a dark area, uncharted.

‘The study of nanoplastics matters because the smaller things are, the more easily they can get inside us.’

The team plans to investigate tap water, which has previously been shown to contain microplastics, although in far smaller quantities than bottled water.

Worldwide, plastic production continues to pose a threat to the environment – with 400 million metric tons produced each year.

More than 30 million tons are dumped yearly in water or on land, and many products made with plastics – such as synthetic clothes – shed particles while being used.

Experts are still working to determine the health effects this can have on humans.

- But a new study finds plastic bottles contain more toxic nanoparticles than tap

- READ MORE: Addiction to drinking from plastic bottles is destroying our planet

By COLIN FERNANDEZ ENVIRONMENT EDITOR and STACY LIBERATORE FOR DAILYMAIL.COM

Bottles of plastic water contain hundreds of thousands of toxic microscopic plastic particles, new research has found.

The findings are likely to shock anyone who has swapped from tap to bottled water, believing it was better for their health.

Drinking water from a bottle could mean you are contaminating your body with tiny bits of plastic, which scientists fear can accumulate in your vital organs with unknown health implications.

Nanoplastics have already been linked to cancer, fertility problems and birth defects.

Scientists using the most advanced laser scanning techniques found an average of 240,000 plastic particles in a one-liter bottle of water, compared to 5.5 per one liter of tap water.

Drinking water from a bottle could mean you are contaminating your body with tiny bits of plastic, which scientists fear can accumulate in your vital organs with unknown implications for health.

Scientists using the most advanced laser scanning techniques found an average of 240,000 plastic particles in a one-liter bottle of water, compared to 5.5 per one-liter of tap water.

University of Columbia researchers tested three popular brands of bottled water sold in the United States – and, using lasers, analyzed the plastic particles they contained down to just 100 nanometers in size.

The particles – nanoplastics - are much smaller than the microplastics previously detected in bottled water.

However, the particles are considered potentially toxic because they are so small that they can enter directly into blood cells and the brain.

These microscopic particles carry phthalates — chemicals that make plastics more durable, flexible, and lasting longer.

Phthalate exposure is attributed to 100,000 premature deaths in the US each year. The chemicals are known to interfere with hormone production in the body.

They are 'linked with developmental, reproductive, brain, immune, and other problems', according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

The highest estimates found 370,000 particles.

Nanoplastics had been too difficult to detect using conventional techniques, which could only find microplastics ranging from 5mm down to 1 micrometer – a millionth of a meter, or 1/25,000th of an inch. Nanoplastic particles are less than 1 micrometer across.

Groundbreaking research in 2018 found around 300 microplastic particles in a liter of bottled water – but researchers were limited by their measurement techniques at the time.

Research is now underway across the world to assess the potentially harmful effects.

The team used a new technique called Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) microscopy, which was recently invented by one of the paper's co-authors.

The method probes bottles with two lasers tuned to make specific molecules resonate, and a computer algorithm determines their origin.

The results showed that nanoparticles made up 90 percent of these molecules, and 10 percent were microplastics.

One common type found of nanoparticle was polyethylene terephthalate or PET.

Scientists using the most advanced laser scanning techniques found an average of 240,000 particles of plastic in a one-liter plastic bottle of water – thousands of times more particles than had been previously found.

Study co-author Professor Beizhan Yan, an environmental chemist at Columbia, said: ‘This was not surprising, since that is what many water bottles are made of,’ said.

He continued: ‘PET is also used for bottled sodas, sports drinks, and products such as ketchup and mayonnaise.

‘It probably gets into the water as bits slough off when the bottle is squeezed or gets exposed to heat.’

Another plastic particle found in bottles of water, and one which outnumbered PET, was polyamide – a type of nylon.

‘Ironically,’ said Professor Yan, ‘this probably comes from plastic filters used to supposedly purify the water before it is bottled.’

The other common plastics found included polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polymethyl methacrylate, all of which are used in various industrial processes.

The tiny particles made up 90 percent of these particles, and 10 percent were microplastics. One common type found was polyethylene terephthalate or PET.

However, the researchers found ‘disturbing’ that these named plastics only accounted for around 10 percent of all the nanoparticles found in the samples. They have no idea what the rest are.

Biophysicist and study co-author Wei Min said the research opens up a new area in science, adding, ‘Previously this was just a dark area, uncharted.

‘The study of nanoplastics matters because the smaller things are, the more easily they can get inside us.’

The team plans to investigate tap water, which has previously been shown to contain microplastics, although in far smaller quantities than bottled water.

Worldwide, plastic production continues to pose a threat to the environment – with 400 million metric tons produced each year.

More than 30 million tons are dumped yearly in water or on land, and many products made with plastics – such as synthetic clothes – shed particles while being used.

Experts are still working to determine the health effects this can have on humans.

🌸

🌸

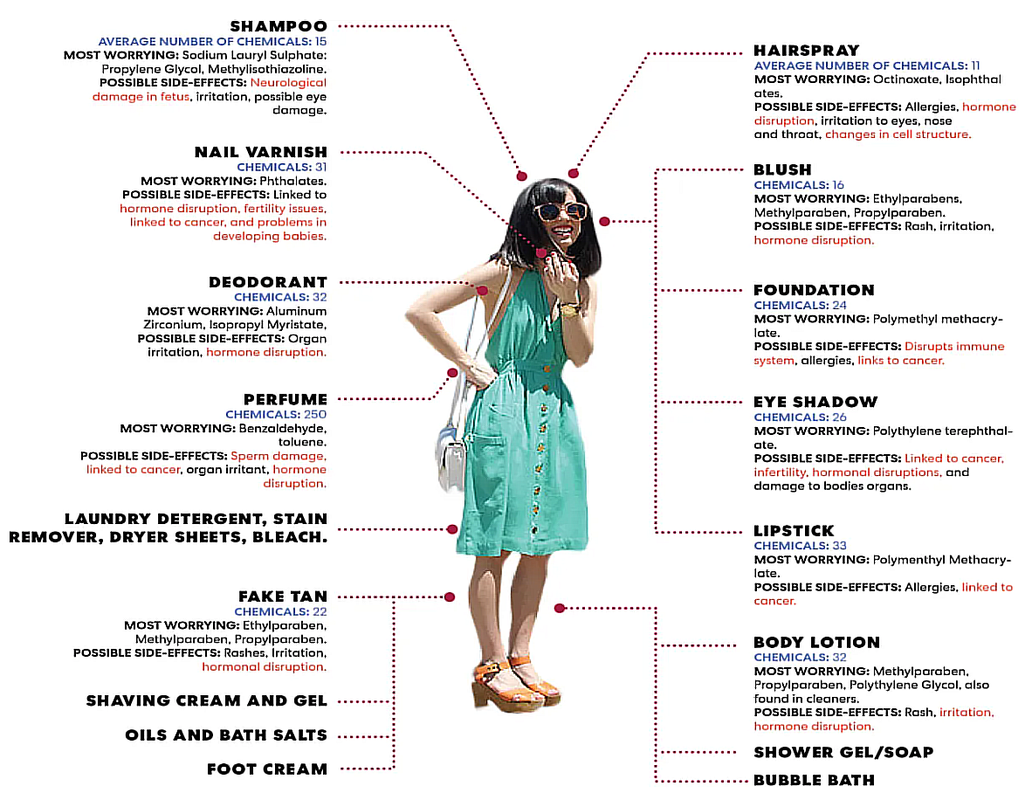

The Women Today

Saturated with

Bisphenols and Phthalates

🌸

The Women Today

Saturated with

Bisphenols and Phthalates

🌸

🌸

Bisphenols and Phthalates

Hormone Disrupters

🌸

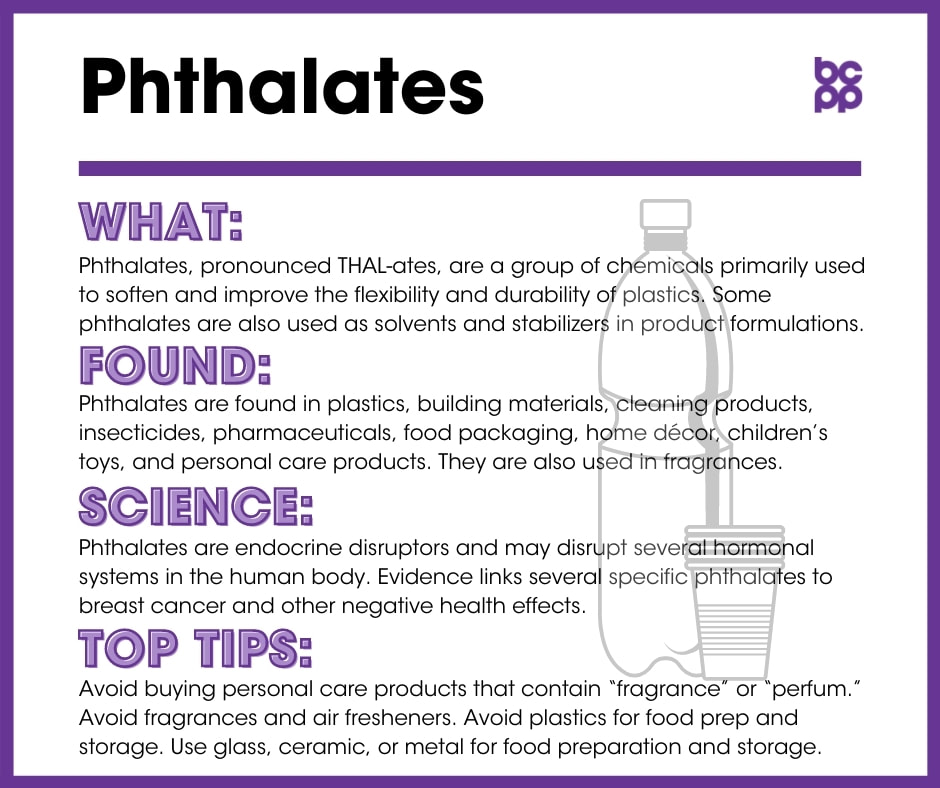

Phthalates are a group of chemicals used to make plastics more durable.

They are often called plasticizers. Some phthalates are used to help dissolve other materials.

🌸

Phthalates are in hundreds of products, such as vinyl flooring, lubricating oils,

and personal-care products (soaps, shampoos, hair sprays).

🌸

Bisphenols and phthalates leach from products into food, water, and dust.

The major route of exposure in humans is through

eating food or drinking water stored in containers made with them.

🌸

Hormone Disrupters

🌸

Phthalates are a group of chemicals used to make plastics more durable.

They are often called plasticizers. Some phthalates are used to help dissolve other materials.

🌸

Phthalates are in hundreds of products, such as vinyl flooring, lubricating oils,

and personal-care products (soaps, shampoos, hair sprays).

🌸

Bisphenols and phthalates leach from products into food, water, and dust.

The major route of exposure in humans is through

eating food or drinking water stored in containers made with them.

🌸

🌸

USE

glass, porcelain or stainless steel

containers and tableware,

particularly for hot food or liquids.

🌸

USE

glass, porcelain or stainless steel

containers and tableware,

particularly for hot food or liquids.

🌸

🌸

These hormone disrupting chemicals are so widely used that

we are constantly exposed.

They can harm our health, even at very low levels.

These hormone disrupting chemicals are so widely used that

we are constantly exposed.

They can harm our health, even at very low levels.

🌸

What are they?

🌸

What are they?

🌸

Bisphenols and phthalates are chemicals that have many uses, including making plastics stronger or more flexible.

Where are they found?

Bisphenols are present in some polycarbonate plastic products (including water bottles, food storage containers and packaging, sports equipment, and compact discs), epoxy resin liners of aluminum cans, and cash register receipts.

Phthalates can be found in some polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic products (including vinyl flooring, shower curtains, toys, plastic wrap, and food packaging and containers), glues, caulks, paints, personal care products, and air fresheners.

What are the health concerns?

Even at low levels, bisphenols and phthalates can mimic or block hormones, disrupting vital body systems. Young children and fetuses are especially vulnerable.

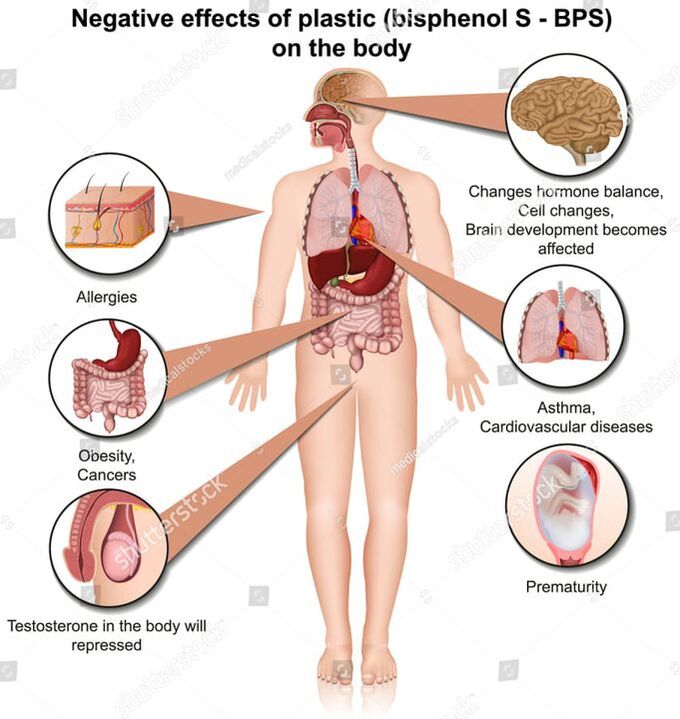

Early life exposure to Bisphenol A (BPA) is linked to asthma and neurodevelopmental problems such as hyperactivity, anxiety, depression, and aggression. In adults, it is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, decreased fertility, and prostate cancer.

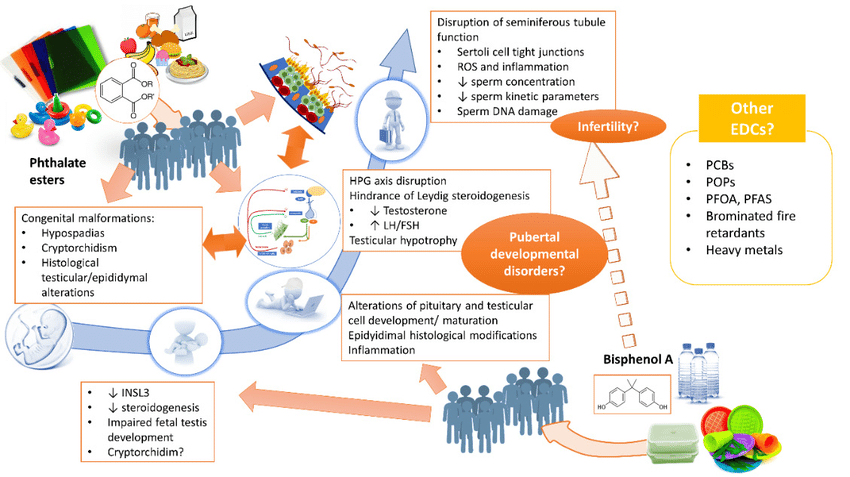

Prenatal and early life exposure to phthalates is linked with asthma, allergies, and cognitive and behavioral problems. It may also affect reproductive development in boys. In adult men, phthalates are associated with reduced fertility.

How are we exposed?

Bisphenols and phthalates leach from products into food, water, and dust. The major route of exposure in humans is through eating food or drinking water stored in containers made with them. We are further exposed through ingesting and inhaling dust and through skin absorption. Bisphenols and phthalates have been detected in the urine of most people tested. Because the body eliminates these chemicals very quickly, this high frequency of detection indicates that our exposure is ubiquitous and continuous.

What are the environmental concerns?

Bisphenols and phthalates enter the environment by leaching from products, manufacturing processes, and recycling. There are substantial amounts of plastic debris containing these chemicals in marine and freshwater ecosystems. As a result, the levels detected in aquatic wildlife are as high or higher than the levels that cause hormone disruption in laboratory animals. The similarities in hormone disruption mechanisms that have been observed between different species suggest that wildlife could be harmed by the same low levels of exposure.

Should they be used?

Many products are now labelled “BPA-free.” However, BPA is often replaced with Bisphenol S (BPS) and Bisphenol F (BPF), which are less studied but appear to have similar hormone-disrupting effects.

The Consumer Product

Safety Commission banned the use of six phthalates in toys and child care products, but they are still widely used in other products, such as food packaging, personal care products and building materials. Like BPA, the phased-out phthalates are often replaced with other phthalates with similar properties and less health information.

What Can You D

Notable Reports

Fact Sheets

News Stories

Where are they found?

Bisphenols are present in some polycarbonate plastic products (including water bottles, food storage containers and packaging, sports equipment, and compact discs), epoxy resin liners of aluminum cans, and cash register receipts.

Phthalates can be found in some polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic products (including vinyl flooring, shower curtains, toys, plastic wrap, and food packaging and containers), glues, caulks, paints, personal care products, and air fresheners.

What are the health concerns?

Even at low levels, bisphenols and phthalates can mimic or block hormones, disrupting vital body systems. Young children and fetuses are especially vulnerable.

Early life exposure to Bisphenol A (BPA) is linked to asthma and neurodevelopmental problems such as hyperactivity, anxiety, depression, and aggression. In adults, it is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, decreased fertility, and prostate cancer.

Prenatal and early life exposure to phthalates is linked with asthma, allergies, and cognitive and behavioral problems. It may also affect reproductive development in boys. In adult men, phthalates are associated with reduced fertility.

How are we exposed?

Bisphenols and phthalates leach from products into food, water, and dust. The major route of exposure in humans is through eating food or drinking water stored in containers made with them. We are further exposed through ingesting and inhaling dust and through skin absorption. Bisphenols and phthalates have been detected in the urine of most people tested. Because the body eliminates these chemicals very quickly, this high frequency of detection indicates that our exposure is ubiquitous and continuous.

What are the environmental concerns?

Bisphenols and phthalates enter the environment by leaching from products, manufacturing processes, and recycling. There are substantial amounts of plastic debris containing these chemicals in marine and freshwater ecosystems. As a result, the levels detected in aquatic wildlife are as high or higher than the levels that cause hormone disruption in laboratory animals. The similarities in hormone disruption mechanisms that have been observed between different species suggest that wildlife could be harmed by the same low levels of exposure.

Should they be used?

Many products are now labelled “BPA-free.” However, BPA is often replaced with Bisphenol S (BPS) and Bisphenol F (BPF), which are less studied but appear to have similar hormone-disrupting effects.

The Consumer Product

Safety Commission banned the use of six phthalates in toys and child care products, but they are still widely used in other products, such as food packaging, personal care products and building materials. Like BPA, the phased-out phthalates are often replaced with other phthalates with similar properties and less health information.

What Can You D

- When possible, opt for glass, porcelain or stainless steel containers and tableware, particularly for hot food or liquids.

- Avoid microwaving plastics.

- Avoid plastic products marked with recycle codes 3 or 7 which may be made with bisphenols or phthalates.

- Eat more fresh food and less canned, packaged, and fast food.

- Avoid handling cash register receipts. If you do touch a cash register receipt, wash your hands afterward.

- Wash your and your children’s hands before eating or drinking.

- Look for fragrance-free personal care products, since the ingredients “fragrance”, “perfume”, or “parfum” often mean phthalates are present.

- Tell regulators and manufacturers that you want products without bisphenols and phthalates when possible.

Notable Reports

- EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals – Five years after their first statement, the Endocrine Society reviewed the increased evidence for the endocrine-disrupting properties of certain chemicals, including bisphenols and phthalates.

- The Parma Consensus Statement on Metabolic Disruptors – This consensus statement asserts that the role of “metabolic disruptor” chemicals ( including BPA and phthalates) in obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome is underestimated and that exposure should be reduced, particularly in early life.

- The Chapel Hill Expert Panel Consensus Statement – This statement by an expert panel of scientists raises concern that humans are chronically exposed to the low levels of BPA at which adverse effects are found in laboratory studies.

Fact Sheets

- Bisphenol A (BPA) Fact Sheet by Biomonitoring California

- Phthalates Fact Sheet by Biomonitoring California

- Exposure to Phthalate Chemicals from Different Dietary Sources (George Washington University)

News Stories

- Sperm Count Zero [Are endocrine disruptors behind falling sperm counts?]. GQ, 9/4/2018

- Is BPA making us fat, anxious and sick? A new effort to find the answer may be falling apart. Huffington Post, 7/20/2018

- The dangerous chemicals found in fast food and restaurants. George Washington U., 3/29/2018

- Canned foods linked to BPA risk in new study. CNN, 6/29/2016

- Fast food serves up phthalates, too, study suggests. CNN, 4/18/2016.

- Chemical in plastics may affect boys’ future fertility. CBS News, 2/19/2015.

- How to avoid products with toxic bisphenol-s. Washington Post, 1/13/2015.

- New study links BPA and childhood asthma. Scientific American, 3/1/2013.

- Special report: the problem with phthalates. Reuters, 10/18/2010

- Mount Sinai Bisphenol A (BPA) fact sheet

- The Chapel Hill Expert Panel Consensus Statement on BPA

- Mount Sinai Phthalates fact sheet

- The Endocrine Society's 2nd Scientific Statement on Endocrine-disrupting Chemicals

🌸

🌸

It's true: Chemicals in common food plastics mimic estrogens in your body, potentially causing fertility problems in men, heart problems in women, and developmental problems in children.

And if you think a "BPA free" label fixes the problem, think again.

We get the latest research from Dr. Scott Belcher of North Carolina State University.

Study finding that most plastics contain estrogenic chemicals: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...

Dr. Scott Belcher: https://tox.sciences.ncsu.edu/people/...

Study showing BPA messes up sperm: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...

One of Dr. Belcher's earliest pieces of published research on BPA hazards: https://academic.oup.com/endo/article...

Study finding BPA causes heart arrhythmias in women: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...

Study finding BPA transfers from women to fetuses: http://www.national-toxic-encephalopa...

Journal article summarizing research on the effects of endocrine disrupters on children: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...

Study finding that Tetra Pak also leaches estrogenic chemicals: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf..

🌸

It's true: Chemicals in common food plastics mimic estrogens in your body, potentially causing fertility problems in men, heart problems in women, and developmental problems in children.

And if you think a "BPA free" label fixes the problem, think again.

We get the latest research from Dr. Scott Belcher of North Carolina State University.

Study finding that most plastics contain estrogenic chemicals: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...

Dr. Scott Belcher: https://tox.sciences.ncsu.edu/people/...

Study showing BPA messes up sperm: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...

One of Dr. Belcher's earliest pieces of published research on BPA hazards: https://academic.oup.com/endo/article...

Study finding BPA causes heart arrhythmias in women: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...

Study finding BPA transfers from women to fetuses: http://www.national-toxic-encephalopa...

Journal article summarizing research on the effects of endocrine disrupters on children: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/arti...

Study finding that Tetra Pak also leaches estrogenic chemicals: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf..

🌸

🌸

An award-winning scientist, her work examines the impact of environmental exposures,

including chemicals such as phthalates and Bisphenol A,

on men’s and women’s reproductive health and the neurodevelopment of children.

🌸

An award-winning scientist, her work examines the impact of environmental exposures,

including chemicals such as phthalates and Bisphenol A,

on men’s and women’s reproductive health and the neurodevelopment of children.

🌸

🌸

The #1 Reason

Humans are Suddenly Being Born

Genderless

🌸

Dr. Shanna Swan

🌸

The #1 Reason

Humans are Suddenly Being Born

Genderless

🌸

Dr. Shanna Swan

🌸

Shanna Swan, Ph.D., is one of the world’s leading environmental and reproductive epidemiologists and a professor of environmental medicine and public health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

https://amzn.to/3XnfeS6

https://www.shannaswan.com https://twitter.com/DrShannaSwan

SPONSORS VERSO - Go to https://ver.so/koncrete to save 15% on your order.

FOLLOW DANNY JONES https://www.instagram.com/jonesdanny https://twitter.com/jonesdanny

LISTEN ON Spotify - https://open.spotify.com/show/4VTLG0H...

https://itunes.apple.com/podcast/id14... JOIN: https://bit.ly/koncretepatreon

OUTLINE

Discovering the global sperm count decline 15:25 -

How pesticide exposure is affecting sperm count 24:22 -

Why sperm banks have extremely high standards 26:24 -

Countries with the best sperm 37:54 -

Lifestyle habits that destroy sperm count 42:06 -

Endocrine disrupting chemicals, phthalates & plastics 46:44 -

Size matters when it comes to your Ano-genital distance (AGD) 1:01:07 -

How phthalates are disrupting hormonal development in babies 1:03:47 -

Correlation between phthalates & gender dysphoria? 1:14:31 -

Testosterone 1:20:47 -

Homosexual frogs study & glyphosate 1:28:37 -

How people can avoid phthalate exposure 1:37:51 -

Population collapse is on the horizon if we don’t start reproducing 1:47:26 -

Animal species facing sperm count & population decline.

https://amzn.to/3XnfeS6

https://www.shannaswan.com https://twitter.com/DrShannaSwan

SPONSORS VERSO - Go to https://ver.so/koncrete to save 15% on your order.

FOLLOW DANNY JONES https://www.instagram.com/jonesdanny https://twitter.com/jonesdanny

LISTEN ON Spotify - https://open.spotify.com/show/4VTLG0H...

https://itunes.apple.com/podcast/id14... JOIN: https://bit.ly/koncretepatreon

OUTLINE

Discovering the global sperm count decline 15:25 -

How pesticide exposure is affecting sperm count 24:22 -

Why sperm banks have extremely high standards 26:24 -

Countries with the best sperm 37:54 -

Lifestyle habits that destroy sperm count 42:06 -

Endocrine disrupting chemicals, phthalates & plastics 46:44 -

Size matters when it comes to your Ano-genital distance (AGD) 1:01:07 -

How phthalates are disrupting hormonal development in babies 1:03:47 -

Correlation between phthalates & gender dysphoria? 1:14:31 -

Testosterone 1:20:47 -

Homosexual frogs study & glyphosate 1:28:37 -

How people can avoid phthalate exposure 1:37:51 -

Population collapse is on the horizon if we don’t start reproducing 1:47:26 -

Animal species facing sperm count & population decline.

🌸

🌸

Phthalates - Bisphenols

and

Homosexuality

🌸

Brían Nguyen Becomes "Miss America’s"

First Transgender Local Title Holder

🌸

https://cerespost.com/brian-nguyen-becomes-miss-americas-first-transgender-local-title-holder/

🌸

Phthalates - Bisphenols

and

Homosexuality

🌸

Brían Nguyen Becomes "Miss America’s"

First Transgender Local Title Holder

🌸

https://cerespost.com/brian-nguyen-becomes-miss-americas-first-transgender-local-title-holder/

🌸

🌸

Phthalates - Bisphenols

and

Homosexuality

🌸

A Trans "Woman" Is Crowned

Miss Netherlands for the First Time

🌸

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/11/world/europe/miss-netherlands-rikkie-valerie-kolle.html

Phthalates - Bisphenols

and

Homosexuality

🌸

A Trans "Woman" Is Crowned

Miss Netherlands for the First Time

🌸

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/11/world/europe/miss-netherlands-rikkie-valerie-kolle.html

🌸

Gestational exposure to phthalates and gender-related ...

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov › articles › PMC4986248

Animal studies have shown that gestational exposure to phthalates

have a de-masculinizing effect on male genitals [12–15], and studies have also ...

🌸

Gestational exposure to phthalates and gender-related ...

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov › articles › PMC4986248

Animal studies have shown that gestational exposure to phthalates

have a de-masculinizing effect on male genitals [12–15], and studies have also ...

🌸

🌸

https://iwaponline.com/jwh/article/19/3/411/81381/

Potential-risk-of-BPA-and-phthalates-in-commercial

🌸

https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Phthalates_FactSheet.html#:~:text=Phthalates%20are%20a%20group%20of,%2C%20shampoos%2C%20hair%20sprays).

🌸

https://iwaponline.com/jwh/article/19/3/411/81381/

Potential-risk-of-BPA-and-phthalates-in-commercial

🌸

https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Phthalates_FactSheet.html#:~:text=Phthalates%20are%20a%20group%20of,%2C%20shampoos%2C%20hair%20sprays).

🌸

| BPA .pdf | |

| File Size: | 437 kb |

| File Type: | |

| Plastics Consumer Factsheet .pdf | |

| File Size: | 204 kb |

| File Type: | |

🌸

🌸

🌸

🌸

🌸

🌸

Phthalates and Bisphenols

🌸

Phthalates and Bisphenols

🌸

Hormone-disrupting chemicals such as phthalates and bisphenols are used to alter the characteristics of plastics, including making plastics more rigid or more flexible. They are so commonly used that they contribute to our Body Burden and can harm our health.

“Body Burden” is the cumulative effect on your body of constant exposure to chemicals of concern from many sources. Your body is burdened by many synthetic chemicals and pollutants ranging from shampoo to skincare products, deodorant, laundry detergent, etc.

The substances may remain present for many years after the exposure has been removed. Oftentimes, building occupants do not realize they are exposed to synthetic chemicals that were created for the building industry and installed in buildings.

“Body Burden” is the cumulative effect on your body of constant exposure to chemicals of concern from many sources. Your body is burdened by many synthetic chemicals and pollutants ranging from shampoo to skincare products, deodorant, laundry detergent, etc.

The substances may remain present for many years after the exposure has been removed. Oftentimes, building occupants do not realize they are exposed to synthetic chemicals that were created for the building industry and installed in buildings.

🌸

Scientists find most silicon rubber kitchenwares

are endocrine disrupting

🌸

Study determines toxicity and composition of 42 silicon rubber food contact articles; finds 84% of silicon kitchenware to induce endocrine activity; review gives update on the known endocrine disruptors phthalates and bisphenols with focus on detection methods

and addressing regulatory concerns;

study develops and applies method for phthalate determination in vegetable oils

https://www.foodpackagingforum.org/news/scientists-find-most-silicon-rubber-kitchenwares-are-endocrine-disrupting

🌸

Scientists find most silicon rubber kitchenwares

are endocrine disrupting

🌸

Study determines toxicity and composition of 42 silicon rubber food contact articles; finds 84% of silicon kitchenware to induce endocrine activity; review gives update on the known endocrine disruptors phthalates and bisphenols with focus on detection methods

and addressing regulatory concerns;

study develops and applies method for phthalate determination in vegetable oils

https://www.foodpackagingforum.org/news/scientists-find-most-silicon-rubber-kitchenwares-are-endocrine-disrupting

🌸

🌸

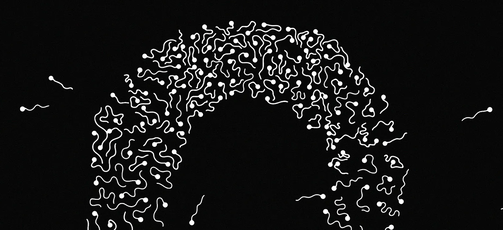

Sperm Count ZERO

https://www.gq.com/story/sperm-count-zero

🌸

Chemical in plastics may affect boys’ future fertility

🌸

Sperm Count ZERO

https://www.gq.com/story/sperm-count-zero

🌸

Chemical in plastics may affect boys’ future fertility

🌸

A strange thing has happened to men over the past few decades: We’ve become increasingly infertile, so much so that within a generation we may lose the ability to reproduce entirely. What’s causing this mysterious drop in sperm counts—and is there any way to reverse it before it’s too late?

By Daniel Noah Halpern

Men are doomed.

Everybody knows this. We're obviously all doomed, the women too, everybody in general, just a waiting game until one or another of the stupid things our stupid species is up to finally gets us. But as it turns out, no surprise: men first. Second instance of no surprise: We're going to take the women down with us.

There has always been evidence that men, throughout life, are at higher risk of early death—from the beginning, a higher male incidence of Death by Mastodon Stomping, a higher incidence of Spiked Club to the Brainpan, a statistically significant disparity between how many men and how many women die of

Accidentally Shooting Themselves in the Face or Getting Really Fat

and Having a Heart Attack.

The male of the species dies younger than the female—about five years on average. Divide a population into groups by birth year, and by the time each cohort reaches 85, there are two women left for every man alive. In fact, the male wins every age class: Baby boys die more often than baby girls; little boys die more often than little girls; teenage boys; young men; middle-aged men. Death champions across the board.

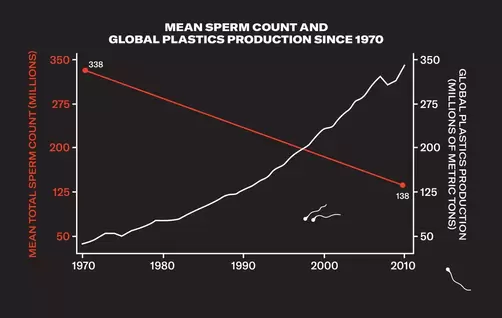

Now it seems that early death isn't enough for us—we're on track instead to void the species entirely. Last summer a group of researchers from Hebrew University and Mount Sinai medical school published a study showing that sperm counts in the U.S., Europe, Australia, and New Zealand have fallen by more than 50 percent over the past four decades. (They judged data from the rest of the world to be insufficient to draw conclusions from, but there are studies suggesting that the trend could be worldwide.) That is to say: We are producing half the sperm our grandfathers did. We are half as fertile.

WATCH

Psychiatrist Breaks Down TV Villain Personality Traits

The Hebrew University/Mount Sinai paper was a meta-analysis by a team of epidemiologists, clinicians, and researchers that culled data from 185 studies, which examined semen from almost 43,000 men. It showed that the human race is apparently on a trend line toward becoming unable to reproduce itself. Sperm counts went from 99 million sperm per milliliter of semen in 1973 to 47 million per milliliter in 2011, and the decline has been accelerating. Would 40 more years—or fewer—bring us all the way to zero?

I called Shanna H. Swan, a reproductive epidemiologist at Mount Sinai and one of the lead authors of the study, to ask if there was any good news hiding behind those brutal numbers. Were we really at risk of extinction? She failed to comfort me.

“The What Does It Mean question means extrapolating beyond your data,” Swan said, “which is always a tricky thing. But you can ask, ‘What does it take? When is a species in danger? When is a species threatened?’ And we are definitely on that path.” That path, in its darkest reaches, leads to no more naturally conceived babies and potentially to no babies at all—and the final generation of Homo sapiens will roam the earth knowing they will be the last of their kind.

If we are half as fertile as the generation before us, why haven't we noticed?

One answer is that there is a lot of redundancy built into reproduction: You don't need 200 million sperm to fertilize an egg, but that's how many the average man might devote to the job. Most men can still conceive a child naturally with a depressed sperm count, and those who can't have a booming fertility-treatment industry ready to help them.

And though lower sperm counts probably have led to a small decrease in the number of children being conceived, that decline has been masked by sociological changes driving birth rates down even faster: People in the developed world are choosing to have fewer children, and they are having them later.

The problem has been debated among fertility scientists for decades now—studies suggesting that sperm counts are declining have been appearing since the '70s—but until Swan and her colleagues' meta-analysis, the results have always been judged incomplete or preliminary. Swan herself had conducted smaller studies on declining sperm counts, but in 2015 she decided it was time for a definitive answer.

She teamed up with Hagai Levine, an Israeli epidemiologist, and Niels Jørgensen, a Danish endocrinologist, and along with five others, they set about performing a systematic review and meta-regression analysis—that is, a kind of statistical synthesis of the data. “Hagai is a very good scientist, and he also used to be the head of epidemiology for the Israeli armed forces,” Swan told me. “So he's very good at organizing.” They spent a year working with the data.

“We should hope for the best and prepare for the worst,” said Hagai Levine, a lead author of the study. “And that is the possibility that we will become extinct.”

The results, when they came in, were clear. Not only were sperm counts per milliliter of semen down by more than 50 percent since 1973, but total sperm counts were down by almost 60 percent: We are producing less semen, and that semen has fewer sperm cells in it.

This time around, even scientists who had been skeptical of past analyses had to admit that the study was all but unassailable. Jørgensen, in Copenhagen, told me that when he saw the results, he'd said aloud, “No, it cannot be true.” He had expected to see a past decline and then a leveling off. But he couldn't argue when the team ran the numbers again and again. The downward slope was unwavering.

Almost all the scientists I talked to stressed that not only were low sperm counts alarming for what they said about the reproductive future of the species—they were also a warning of a much larger set of health problems facing men. In this view, sperm production is a canary in the coal mine of male bodies: We know, for instance, that men with poor semen quality have a higher mortality rate and are more likely to have diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease than fertile men.

Testosterone levels have also dropped precipitously, with effects beginning in utero and extending into adulthood. One of the most significant markers of an organism's sex is something called anogenital distance (AGD)—the measurement between the anus and the genitals. Male AGD is typically twice the length of female, a much more dramatic difference than height or weight or musculature.

Lower testosterone leads to a shorter AGD, and a measurement lower than the median correlates to a man being seven times as likely to be subfertile and gives him a greater likelihood of having undescended testicles, testicular tumors, and a smaller penis. “What you are seeing in a number of systems, other developmental systems, is that the sex differences are shrinking,” Swan told me. Men are producing less sperm. They're also becoming less male.

I assumed that the next thing Swan was going to tell me was that these changes were all a mystery to scientists. If only we could figure out what was causing the drop in sperm counts, I imagined, we could solve all the attendant health problems at once. But it turns out that it's not a mystery: We know what the culprit is. And it's hiding in plain sight.

The sixth floor of the Rigshospitalet, a hospital and research institution in Copenhagen, houses the Department of Growth and Reproduction. The babies are all a few floors downstairs—on six, the unit is populated not with new parents but with doctors and researchers hunched over mass spectrometers and gel imagers and the like.

I was there to meet Niels E. Skakkebæk, an 82-year-old pediatric endocrinologist, who founded the department in 1990. After walking me through the lab, he showed me to his office, a cramped, closet-like space—modest for someone who is a giant in his field. Male fertility and male reproductive health, Skakkebæk told me, are in full-blown crisis. “Here in Denmark, there is an epidemic of infertility,” he said. “More than 20 percent of Danish men do not father children.”

Skakkebæk first suspected something was going wrong in the late '70s, when he treated an infertile patient with an abnormality in the cells of the testes that he had never seen before. When he treated a second man with the same abnormality a few years later, he began to investigate a connection. What he found was a new form of precursor cells for testicular cancer, a once rare disease whose incidence had doubled.

Moreover, these precursor cells had begun developing before the patient was even born. “He had the insight that testicular cancer, which is a cancer of young men, is something that is actually originated in utero,” Swan told me. And if these testes had somehow been misdeveloping in utero, Skakkebæk asked himself, what else was happening to these babies before they were born?

Eventually, Skakkebæk linked several other previously rare symptoms for a condition he called testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS), a collection of male reproductive problems that include hypospadias (an abnormal location for the end of the urethra), cryptorchidism (an undescended testicle), poor semen quality, and testicular cancer. What Skakkebæk proposed with TDS is that these disorders can have a common fetal origin, a disruption in the development of the male fetus in the womb.

So what was causing this disruption? To say there is only a single answer might be an overstatement—stress, smoking, and obesity, for example, all depress sperm counts—but there are fewer and fewer critics of the following theory: The industrial revolution happened. And the oil industry happened. And 20th-century chemistry happened. In short, humans started ingesting a whole host of compounds that affected our hormones—including, most crucially, estrogen and testosterone.

By Daniel Noah Halpern

Men are doomed.

Everybody knows this. We're obviously all doomed, the women too, everybody in general, just a waiting game until one or another of the stupid things our stupid species is up to finally gets us. But as it turns out, no surprise: men first. Second instance of no surprise: We're going to take the women down with us.

There has always been evidence that men, throughout life, are at higher risk of early death—from the beginning, a higher male incidence of Death by Mastodon Stomping, a higher incidence of Spiked Club to the Brainpan, a statistically significant disparity between how many men and how many women die of

Accidentally Shooting Themselves in the Face or Getting Really Fat

and Having a Heart Attack.

The male of the species dies younger than the female—about five years on average. Divide a population into groups by birth year, and by the time each cohort reaches 85, there are two women left for every man alive. In fact, the male wins every age class: Baby boys die more often than baby girls; little boys die more often than little girls; teenage boys; young men; middle-aged men. Death champions across the board.

Now it seems that early death isn't enough for us—we're on track instead to void the species entirely. Last summer a group of researchers from Hebrew University and Mount Sinai medical school published a study showing that sperm counts in the U.S., Europe, Australia, and New Zealand have fallen by more than 50 percent over the past four decades. (They judged data from the rest of the world to be insufficient to draw conclusions from, but there are studies suggesting that the trend could be worldwide.) That is to say: We are producing half the sperm our grandfathers did. We are half as fertile.

WATCH

Psychiatrist Breaks Down TV Villain Personality Traits

The Hebrew University/Mount Sinai paper was a meta-analysis by a team of epidemiologists, clinicians, and researchers that culled data from 185 studies, which examined semen from almost 43,000 men. It showed that the human race is apparently on a trend line toward becoming unable to reproduce itself. Sperm counts went from 99 million sperm per milliliter of semen in 1973 to 47 million per milliliter in 2011, and the decline has been accelerating. Would 40 more years—or fewer—bring us all the way to zero?

I called Shanna H. Swan, a reproductive epidemiologist at Mount Sinai and one of the lead authors of the study, to ask if there was any good news hiding behind those brutal numbers. Were we really at risk of extinction? She failed to comfort me.

“The What Does It Mean question means extrapolating beyond your data,” Swan said, “which is always a tricky thing. But you can ask, ‘What does it take? When is a species in danger? When is a species threatened?’ And we are definitely on that path.” That path, in its darkest reaches, leads to no more naturally conceived babies and potentially to no babies at all—and the final generation of Homo sapiens will roam the earth knowing they will be the last of their kind.

If we are half as fertile as the generation before us, why haven't we noticed?

One answer is that there is a lot of redundancy built into reproduction: You don't need 200 million sperm to fertilize an egg, but that's how many the average man might devote to the job. Most men can still conceive a child naturally with a depressed sperm count, and those who can't have a booming fertility-treatment industry ready to help them.

And though lower sperm counts probably have led to a small decrease in the number of children being conceived, that decline has been masked by sociological changes driving birth rates down even faster: People in the developed world are choosing to have fewer children, and they are having them later.

The problem has been debated among fertility scientists for decades now—studies suggesting that sperm counts are declining have been appearing since the '70s—but until Swan and her colleagues' meta-analysis, the results have always been judged incomplete or preliminary. Swan herself had conducted smaller studies on declining sperm counts, but in 2015 she decided it was time for a definitive answer.

She teamed up with Hagai Levine, an Israeli epidemiologist, and Niels Jørgensen, a Danish endocrinologist, and along with five others, they set about performing a systematic review and meta-regression analysis—that is, a kind of statistical synthesis of the data. “Hagai is a very good scientist, and he also used to be the head of epidemiology for the Israeli armed forces,” Swan told me. “So he's very good at organizing.” They spent a year working with the data.

“We should hope for the best and prepare for the worst,” said Hagai Levine, a lead author of the study. “And that is the possibility that we will become extinct.”

The results, when they came in, were clear. Not only were sperm counts per milliliter of semen down by more than 50 percent since 1973, but total sperm counts were down by almost 60 percent: We are producing less semen, and that semen has fewer sperm cells in it.

This time around, even scientists who had been skeptical of past analyses had to admit that the study was all but unassailable. Jørgensen, in Copenhagen, told me that when he saw the results, he'd said aloud, “No, it cannot be true.” He had expected to see a past decline and then a leveling off. But he couldn't argue when the team ran the numbers again and again. The downward slope was unwavering.

Almost all the scientists I talked to stressed that not only were low sperm counts alarming for what they said about the reproductive future of the species—they were also a warning of a much larger set of health problems facing men. In this view, sperm production is a canary in the coal mine of male bodies: We know, for instance, that men with poor semen quality have a higher mortality rate and are more likely to have diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease than fertile men.

Testosterone levels have also dropped precipitously, with effects beginning in utero and extending into adulthood. One of the most significant markers of an organism's sex is something called anogenital distance (AGD)—the measurement between the anus and the genitals. Male AGD is typically twice the length of female, a much more dramatic difference than height or weight or musculature.

Lower testosterone leads to a shorter AGD, and a measurement lower than the median correlates to a man being seven times as likely to be subfertile and gives him a greater likelihood of having undescended testicles, testicular tumors, and a smaller penis. “What you are seeing in a number of systems, other developmental systems, is that the sex differences are shrinking,” Swan told me. Men are producing less sperm. They're also becoming less male.

I assumed that the next thing Swan was going to tell me was that these changes were all a mystery to scientists. If only we could figure out what was causing the drop in sperm counts, I imagined, we could solve all the attendant health problems at once. But it turns out that it's not a mystery: We know what the culprit is. And it's hiding in plain sight.

The sixth floor of the Rigshospitalet, a hospital and research institution in Copenhagen, houses the Department of Growth and Reproduction. The babies are all a few floors downstairs—on six, the unit is populated not with new parents but with doctors and researchers hunched over mass spectrometers and gel imagers and the like.

I was there to meet Niels E. Skakkebæk, an 82-year-old pediatric endocrinologist, who founded the department in 1990. After walking me through the lab, he showed me to his office, a cramped, closet-like space—modest for someone who is a giant in his field. Male fertility and male reproductive health, Skakkebæk told me, are in full-blown crisis. “Here in Denmark, there is an epidemic of infertility,” he said. “More than 20 percent of Danish men do not father children.”

Skakkebæk first suspected something was going wrong in the late '70s, when he treated an infertile patient with an abnormality in the cells of the testes that he had never seen before. When he treated a second man with the same abnormality a few years later, he began to investigate a connection. What he found was a new form of precursor cells for testicular cancer, a once rare disease whose incidence had doubled.

Moreover, these precursor cells had begun developing before the patient was even born. “He had the insight that testicular cancer, which is a cancer of young men, is something that is actually originated in utero,” Swan told me. And if these testes had somehow been misdeveloping in utero, Skakkebæk asked himself, what else was happening to these babies before they were born?

Eventually, Skakkebæk linked several other previously rare symptoms for a condition he called testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS), a collection of male reproductive problems that include hypospadias (an abnormal location for the end of the urethra), cryptorchidism (an undescended testicle), poor semen quality, and testicular cancer. What Skakkebæk proposed with TDS is that these disorders can have a common fetal origin, a disruption in the development of the male fetus in the womb.

So what was causing this disruption? To say there is only a single answer might be an overstatement—stress, smoking, and obesity, for example, all depress sperm counts—but there are fewer and fewer critics of the following theory: The industrial revolution happened. And the oil industry happened. And 20th-century chemistry happened. In short, humans started ingesting a whole host of compounds that affected our hormones—including, most crucially, estrogen and testosterone.

🌸

🌸

The scientists I talked to were less cautious about embracing this explanation than I expected. Down the hall from Skakkebæk's office, I met Anna-Maria Andersson, a biologist whose research has focused on declining testosterone levels. “There has been a chemical revolution going on starting from the beginning of the 19th century, maybe even a bit before,” she told me, “and upwards and exploding after the Second World War, when hundreds of new chemicals came onto the market within a very short time frame.”

Suddenly a vast array of chemicals were entering our bloodstream, ones that no human body had ever had to deal with. The chemical revolution gave us some wonderful things: new medicines, new food sources, faster and cheaper mass production of all sorts of necessary products. It also gave us, Andersson pointed out, a living experiment on the human body with absolutely no forethought to the result.

When a chemical affects your hormones, it's called an endocrine disruptor. And it turns out that many of the compounds used to make plastic soft and flexible (like phthalates) or to make them harder and stronger (like Bisphenol A, or BPA) are consummate endocrine disruptors. Phthalates and BPA, for example, mimic estrogen in the bloodstream. If you're a man with a lot of phthalates in his system, you'll produce less testosterone and fewer sperm. If exposed to phthalates in utero, a male fetus's reproductive system itself will be altered: He will develop to be less male.

Women with raised levels of phthalates in their urine during pregnancy were significantly more likely to have sons with shorter anogenital distance as well as shorter penis length and smaller testes. “When the [fetus's] testicles start making testosterone, which is about week eight of pregnancy, they make a little less,” Swan said. “That's the nub of this whole story. So phthalates decrease testosterone. The testicles then do not produce proper testosterone, and the anogenital distance is shorter.”

The problem is that these chemicals are everywhere. BPA can be found in water bottles and food containers and sales receipts. Phthalates are even more common: They are in the coatings of pills and nutritional supplements; they're used in gelling agents, lubricants, binders, emulsifying agents, and suspending agents.

Not to mention medical devices, detergents and packaging, paint and modeling clay, pharmaceuticals and textiles and sex toys and nail polish and liquid soap and hair spray. They are used in tubing that processes food, so you'll find them in milk, yogurt, sauces, soups, and even, in small amounts, in eggs, fruits, vegetables, pasta, noodles, rice, and water. The CDC determined that just about everyone in the United States has measurable levels of phthalates in his or her body—they're unavoidable.

What's more, there is evidence that the effect of these endocrine disruptors increases over generations, due to something called epigenetic inheritance. Normally, acquired traits—like, say, a sperm count lowered by obesity—aren't passed down from father to son.

But some chemicals, including phthalates and BPA, can change the way genes are expressed without altering the underlying genetic code, and that change is inheritable. Your father passes along his low sperm count to you, and your sperm count goes even lower after you're exposed to endocrine disruptors. That's part of the reason there's been no leveling off even after 40 years of declining sperm counts—the baseline keeps dropping.

With all due respect to Dr. Swan and the problems of extrapolating beyond one's data, I wanted to get back to What It All Means. The answer, I thought, might be found at the 13th International Symposium on Spermatology, which took place in May, on Lidingö, a small island in the inner Stockholm archipelago.

A hundred spermatologists in one place: You'd think (incorrectly) that the jokes would be good. Skakkebæk had told me I'd be able to find some dissenters to the conclusions of Swan's meta-analysis there, but what I witnessed instead was the final vanquishing of the few remaining doubters.

At the welcome dinner (reindeer and rooster), I met Hagai Levine, the Israeli co-author of the Hebrew University/Mount Sinai meta-analysis. Levine, who is 40, told me we had reasons to worry. “I'm saying that we should hope for the best and prepare for the worst,” he said. “And that is the possibility that we will become extinct. That's a possibility we must seriously consider. I'm not saying it's going to happen. I'm not saying it's likely to happen. I'm not saying that's the prediction. I'm just saying we should be prepared for such a possibility. That's all. And we are not.”

His session the next morning—“Are Spermatozoa at the Verge of Extinction?”—would be the defining event of the conference: It cast a shadow over all the other talks. At a panel discussion that followed his presentation, Levine continued his argument for addressing the causes of the crisis, saying, “My default, if I don't know, is that it is up to the manufacturers of chemicals to prove that their chemicals are safe. But I don't feel like I need any more evidence to take action with chemicals already known to disrupt the endocrine system.”

The organizer of the symposium, Lars Björndahl, a Swedish spermatologist who had presented earlier in the morning, urged caution. “I have great respect for epidemiological studies, but we should remember that mathematical correlations don't prove that there is a causative relation,” he said.

Questions from the audience—often taking the form of statements—were much along the same lines: Be careful of a bias toward the assumption that all these things are connected. Levine nodded with only a hint of chagrin, like a patient professor waiting hopefully for his students to catch up.

Sign Up For The GQ Wellness NewsletterA weekly dose of practical advice from experts on healthy habits, happy relationships and fitness hacks for normal people.

By subscribing you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement.

David Mortimer, who runs a company that designs and establishes assisted-conception laboratories, was one of the only members of the audience willing to question Levine's study itself. He pointed out that methods for measuring sperm had changed dramatically over the time period of the study and that the old studies were profoundly unreliable.

Levine was ready with an answer. “So that's one of the reasons we also conducted a sensitivity analysis,” he said from the stage, “with studies with sample collection only after 1995—and the slope was even steeper. So that could not explain the decline we see after 1995.”

“I've never said there was no decline in sperm counts,” Mortimer said, a bit defensively. Levine, who had been so gracious and engaged with his critics, began to look a little tired. He rallied, though, when the group agreed to put out a joint statement about the crisis. The chairs of the symposium called on the world to acknowledge that male reproductive health was essential for the survival of the species, that its decline was alarming and should be studied, and that at present it was being neglected in funding and attention.

Mortimer came around and ended up signing the statement. When I caught up with him later, he wasn't nearly as dismissive of the study's conclusions as I expected. He agreed there was little question that sperm counts were dropping, and he even embraced some of the direst predictions of scientists like Levine.

“The epigenetics are the scary bit,” he told me, “because what we're doing now affects the future of the human race.” When even the skeptics are scared, it's probably time to pay attention.

Can anything be done?

Over the past 20 years, there have been occasional attempts to limit the number of endocrine disruptors in circulation, but inevitably the fixes are insubstantial: one chemical removed in favor of another, which eventually turns out to have its own dangers. That was the case with BPA, which was partly replaced by Bisphenol S, which might be even worse for you.

The chemical industry, unsurprisingly, has been resistant to the notion that the billions of dollars of revenue these products represent might also represent terrible damage to the human body, and have often followed the model of Big Tobacco and Big Oil—fighting regulation with lobbyists and funding their own studies that suggest their products are harmless.

The website for the American Chemistry Council, an industry trade association, has a page dedicated to phthalates that mostly consists of calling Shanna Swan's research “controversial” and asserting that her “use of methodologies that have not been validated and unconventional data analysis have been criticized by the scientific community.”

(Cited critics of Swan include Elizabeth Whelan, now deceased, an epidemiologist famous for fighting the regulation of chemicals from her position as president of the American Council on Science and Health, which has received funding from Chevron, DuPont, and other companies in the plastic business.)

Assuming that we're unable to wean ourselves off plastics and other marvels of modern science, we may be stuck innovating our way out of this mess. How long we're able to outrun the drop in sperm count may depend, finally, on how good we get at IVF and other fertility treatments.

When I spoke with Marc Goldstein, a urologist and surgeon at Weill Cornell medical center in New York City, he said that while there was “no question I've seen a big increase in men with male-factor infertility,” he wasn't worried for the future of the species. Assisted reproduction would keep the babies coming, no matter how sickly men's sperm become.

It's true that fertility treatments have already given men with extremely low sperm counts the chance to be fathers. Indeed, by looking at their cases, we can glimpse what our low-sperm-count future might look like. We know that it will be arduous to conceive, and expensive—so expensive that having children may no longer be an option available to all couples. A fertility-treatment-dependent future is also unlikely to produce a birth rate anywhere near current levels.

Not long ago, I spoke with Chris Wohl, a research materials/surface engineer at the NASA Langley Research Center in Virginia, who spent six years trying to conceive a child. Both he and his wife had fertility problems: Wohl's sperm count was under 2 million per milliliter—the average count we'd expect to reach, at the current rate, by 2034. “We started in the normal way of trying to have kids,” he said, “and after a few years, we said, ‘Okay, let's talk to some folks.’ ” They went through several rounds of intrauterine insemination.

“And then after that sixth time, we said, ‘This isn't working. We need to kind of up our technology game.’ So we went to a reproductive endocrinologist and went through several rounds of IVF. And then when that failed, we were going to look into adoption. That's when somebody came forward and said that they would be a surrogate for us.” Finally, with the surrogate, the process worked. He and his wife now have a healthy, strong-willed 4-year-old girl.

So perhaps that's the solution: As long as we hover somewhere above Sperm Count Zero, and with an assist from modern medicine, we have a shot. Men will continue to be essential to the survival of the species. The problem with innovation, though, is that it never stops.

A new technology known as IVG—in vitro gametogenesis—is showing early promise at turning embryonic stem cells into sperm. In 2016, Japanese scientists created baby mice by fertilizing normal mouse eggs with sperm created via IVG. The stem cells in question were taken from female mice. There was no need for any males.

Daniel Noah Halpern wrote about the Singularity in the November 2014 issue.

This story originally appeared in the September 2018 issue with the title "Sperm Count Zero."

Suddenly a vast array of chemicals were entering our bloodstream, ones that no human body had ever had to deal with. The chemical revolution gave us some wonderful things: new medicines, new food sources, faster and cheaper mass production of all sorts of necessary products. It also gave us, Andersson pointed out, a living experiment on the human body with absolutely no forethought to the result.

When a chemical affects your hormones, it's called an endocrine disruptor. And it turns out that many of the compounds used to make plastic soft and flexible (like phthalates) or to make them harder and stronger (like Bisphenol A, or BPA) are consummate endocrine disruptors. Phthalates and BPA, for example, mimic estrogen in the bloodstream. If you're a man with a lot of phthalates in his system, you'll produce less testosterone and fewer sperm. If exposed to phthalates in utero, a male fetus's reproductive system itself will be altered: He will develop to be less male.

Women with raised levels of phthalates in their urine during pregnancy were significantly more likely to have sons with shorter anogenital distance as well as shorter penis length and smaller testes. “When the [fetus's] testicles start making testosterone, which is about week eight of pregnancy, they make a little less,” Swan said. “That's the nub of this whole story. So phthalates decrease testosterone. The testicles then do not produce proper testosterone, and the anogenital distance is shorter.”

The problem is that these chemicals are everywhere. BPA can be found in water bottles and food containers and sales receipts. Phthalates are even more common: They are in the coatings of pills and nutritional supplements; they're used in gelling agents, lubricants, binders, emulsifying agents, and suspending agents.

Not to mention medical devices, detergents and packaging, paint and modeling clay, pharmaceuticals and textiles and sex toys and nail polish and liquid soap and hair spray. They are used in tubing that processes food, so you'll find them in milk, yogurt, sauces, soups, and even, in small amounts, in eggs, fruits, vegetables, pasta, noodles, rice, and water. The CDC determined that just about everyone in the United States has measurable levels of phthalates in his or her body—they're unavoidable.

What's more, there is evidence that the effect of these endocrine disruptors increases over generations, due to something called epigenetic inheritance. Normally, acquired traits—like, say, a sperm count lowered by obesity—aren't passed down from father to son.

But some chemicals, including phthalates and BPA, can change the way genes are expressed without altering the underlying genetic code, and that change is inheritable. Your father passes along his low sperm count to you, and your sperm count goes even lower after you're exposed to endocrine disruptors. That's part of the reason there's been no leveling off even after 40 years of declining sperm counts—the baseline keeps dropping.

With all due respect to Dr. Swan and the problems of extrapolating beyond one's data, I wanted to get back to What It All Means. The answer, I thought, might be found at the 13th International Symposium on Spermatology, which took place in May, on Lidingö, a small island in the inner Stockholm archipelago.

A hundred spermatologists in one place: You'd think (incorrectly) that the jokes would be good. Skakkebæk had told me I'd be able to find some dissenters to the conclusions of Swan's meta-analysis there, but what I witnessed instead was the final vanquishing of the few remaining doubters.

At the welcome dinner (reindeer and rooster), I met Hagai Levine, the Israeli co-author of the Hebrew University/Mount Sinai meta-analysis. Levine, who is 40, told me we had reasons to worry. “I'm saying that we should hope for the best and prepare for the worst,” he said. “And that is the possibility that we will become extinct. That's a possibility we must seriously consider. I'm not saying it's going to happen. I'm not saying it's likely to happen. I'm not saying that's the prediction. I'm just saying we should be prepared for such a possibility. That's all. And we are not.”

His session the next morning—“Are Spermatozoa at the Verge of Extinction?”—would be the defining event of the conference: It cast a shadow over all the other talks. At a panel discussion that followed his presentation, Levine continued his argument for addressing the causes of the crisis, saying, “My default, if I don't know, is that it is up to the manufacturers of chemicals to prove that their chemicals are safe. But I don't feel like I need any more evidence to take action with chemicals already known to disrupt the endocrine system.”

The organizer of the symposium, Lars Björndahl, a Swedish spermatologist who had presented earlier in the morning, urged caution. “I have great respect for epidemiological studies, but we should remember that mathematical correlations don't prove that there is a causative relation,” he said.

Questions from the audience—often taking the form of statements—were much along the same lines: Be careful of a bias toward the assumption that all these things are connected. Levine nodded with only a hint of chagrin, like a patient professor waiting hopefully for his students to catch up.

Sign Up For The GQ Wellness NewsletterA weekly dose of practical advice from experts on healthy habits, happy relationships and fitness hacks for normal people.

By subscribing you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement.

David Mortimer, who runs a company that designs and establishes assisted-conception laboratories, was one of the only members of the audience willing to question Levine's study itself. He pointed out that methods for measuring sperm had changed dramatically over the time period of the study and that the old studies were profoundly unreliable.

Levine was ready with an answer. “So that's one of the reasons we also conducted a sensitivity analysis,” he said from the stage, “with studies with sample collection only after 1995—and the slope was even steeper. So that could not explain the decline we see after 1995.”

“I've never said there was no decline in sperm counts,” Mortimer said, a bit defensively. Levine, who had been so gracious and engaged with his critics, began to look a little tired. He rallied, though, when the group agreed to put out a joint statement about the crisis. The chairs of the symposium called on the world to acknowledge that male reproductive health was essential for the survival of the species, that its decline was alarming and should be studied, and that at present it was being neglected in funding and attention.

Mortimer came around and ended up signing the statement. When I caught up with him later, he wasn't nearly as dismissive of the study's conclusions as I expected. He agreed there was little question that sperm counts were dropping, and he even embraced some of the direst predictions of scientists like Levine.

“The epigenetics are the scary bit,” he told me, “because what we're doing now affects the future of the human race.” When even the skeptics are scared, it's probably time to pay attention.

Can anything be done?

Over the past 20 years, there have been occasional attempts to limit the number of endocrine disruptors in circulation, but inevitably the fixes are insubstantial: one chemical removed in favor of another, which eventually turns out to have its own dangers. That was the case with BPA, which was partly replaced by Bisphenol S, which might be even worse for you.

The chemical industry, unsurprisingly, has been resistant to the notion that the billions of dollars of revenue these products represent might also represent terrible damage to the human body, and have often followed the model of Big Tobacco and Big Oil—fighting regulation with lobbyists and funding their own studies that suggest their products are harmless.

The website for the American Chemistry Council, an industry trade association, has a page dedicated to phthalates that mostly consists of calling Shanna Swan's research “controversial” and asserting that her “use of methodologies that have not been validated and unconventional data analysis have been criticized by the scientific community.”

(Cited critics of Swan include Elizabeth Whelan, now deceased, an epidemiologist famous for fighting the regulation of chemicals from her position as president of the American Council on Science and Health, which has received funding from Chevron, DuPont, and other companies in the plastic business.)

Assuming that we're unable to wean ourselves off plastics and other marvels of modern science, we may be stuck innovating our way out of this mess. How long we're able to outrun the drop in sperm count may depend, finally, on how good we get at IVF and other fertility treatments.

When I spoke with Marc Goldstein, a urologist and surgeon at Weill Cornell medical center in New York City, he said that while there was “no question I've seen a big increase in men with male-factor infertility,” he wasn't worried for the future of the species. Assisted reproduction would keep the babies coming, no matter how sickly men's sperm become.

It's true that fertility treatments have already given men with extremely low sperm counts the chance to be fathers. Indeed, by looking at their cases, we can glimpse what our low-sperm-count future might look like. We know that it will be arduous to conceive, and expensive—so expensive that having children may no longer be an option available to all couples. A fertility-treatment-dependent future is also unlikely to produce a birth rate anywhere near current levels.

Not long ago, I spoke with Chris Wohl, a research materials/surface engineer at the NASA Langley Research Center in Virginia, who spent six years trying to conceive a child. Both he and his wife had fertility problems: Wohl's sperm count was under 2 million per milliliter—the average count we'd expect to reach, at the current rate, by 2034. “We started in the normal way of trying to have kids,” he said, “and after a few years, we said, ‘Okay, let's talk to some folks.’ ” They went through several rounds of intrauterine insemination.

“And then after that sixth time, we said, ‘This isn't working. We need to kind of up our technology game.’ So we went to a reproductive endocrinologist and went through several rounds of IVF. And then when that failed, we were going to look into adoption. That's when somebody came forward and said that they would be a surrogate for us.” Finally, with the surrogate, the process worked. He and his wife now have a healthy, strong-willed 4-year-old girl.

So perhaps that's the solution: As long as we hover somewhere above Sperm Count Zero, and with an assist from modern medicine, we have a shot. Men will continue to be essential to the survival of the species. The problem with innovation, though, is that it never stops.

A new technology known as IVG—in vitro gametogenesis—is showing early promise at turning embryonic stem cells into sperm. In 2016, Japanese scientists created baby mice by fertilizing normal mouse eggs with sperm created via IVG. The stem cells in question were taken from female mice. There was no need for any males.

Daniel Noah Halpern wrote about the Singularity in the November 2014 issue.

This story originally appeared in the September 2018 issue with the title "Sperm Count Zero."

🌸

🌸

🌸